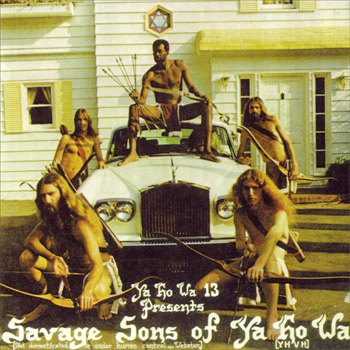

Ya Ho Wa 13 “Savage Sons”

When discussing obscure rock and roll bands from the 1960s, you often find yourself mired in the same old backstory; local band starts out in some cat’s garage and tries on Beatles and Stones songs for size until they finally meet Sgt. Pepper, turn on with the rest of the country, chip in for a sitar and some guitar effects, and start getting metaphysical. Fortunately, however, you will occasionally get a group of musicians that has a tale far more interesting and unique “ such as Ya Ho Wa 13.

Formed not out of someone’s garage but out of someone’s cult, Ya Ho Wa 13 was the house band for the Source Family commune, a tight-knit group of wayfaring strangers under the tutelage of health food restauranteur and ex-Nature Boy Jim Baker, alias Father Yod. With Yod at the helm, the group spent the late 1960s and early 1970s recording a series of wildly eccentric albums of cosmic improvisation, philosophical earth-child hymns and pounding drums. Though many of these records remain almost overwhelmingly anti-commercial and generally inaccessible to the general listener (wait, who?), their 1974 record Savage Sons of Ya Ho Wa brims with strong songs and righteous grooves, and comes highly recommended to all fans of underground American rock and roll.

It is perhaps telling that musical accessibility first arrives with Father Yod taking a backseat to the proceedings and allowing members of the Source Family to contribute their own material. Though the band itself remains constant here “ Djin and Rhythm Aquarian on the guitars, Sunflower Aquarian on bass, and Octavius Aquarian on drums “ the lead vocals are handled by whoever contributed the song. This gives each cut an individuality that really keeps things burning, and allows for a consistently exciting listen. The two strongest voices here are Electron Aquarian’s frenzied growl on cuts likeFire in the Sky and Man the Messiah, and what I believe is Djin Aquarian channeling Topanga-era Neil Young on Red River Valley, among several others. The music here is definitely in the old west coast tradition, full of weird, chiming guitars, fiery San Francisco style leads and raw jams. In fact, this is some of the best of this type of music I think I’ve ever heard, with the record’s backwoods production helping to ground the band’s most lysergic explorations. The band is real tight, with a funky back-beat over which Djin’s guitar weaves transcendental “ check out his playing on the seven minute odyssey A Thousand Sighs, as brother Electron drips cosmic soul across lyrics like the church, the archive/with rules contrived/the truth you hide.

Unfortunately, Savage Sons is one of several Ya Ho Wa 13 recordings to remain out-of-print, released in limited number on vinyl, and only being reissued once in 1999 when former Source family member Sky Saxon oversaw the release of the six-disc God and Hair box set. Until someone oversees a proper re-release of this album on its own, you’re going to have to try and track down either that box set or one of those 500-1000 existing original copies. Meanwhile, you can learn more about this unique group and the people behind it by checking out Isis Aquarian’s great book The Source.

“The Edge of A Dream”

![]() Original | 1974 | Higher Key Records | search ebay ]

Original | 1974 | Higher Key Records | search ebay ]