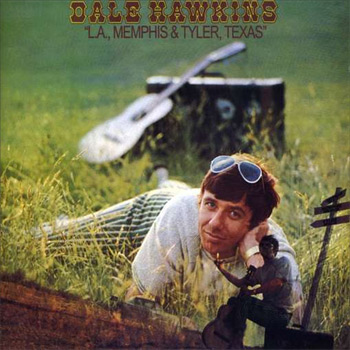

Dale Hawkins “L.A, Memphis, and Tyler, Texas”

Dale Hawkins, cousin of the legendary rockabilly raver Ronnie Hawkins, is most commonly remembered for writing and recording the original version of the swamp-rock standard “Suzie Q” in 1957. Born and raised in Louisiana, Hawkins had reached a milestone at the beginning of his career by bringing the sound of the swamp to the masses. However, Hawkins was much more than just a writer or a singer, and he spent the next ten years recording more singles for Chess Records and working behind the scenes as a producer and A&R man.

By 1967 Hawkins was itchin’ to cut an lp of his own again and headed into a small studio in Los Angeles where, he began work on what was to become L.A, Memphis, & Tyler, Texas. Holed up in bassist Joe Osborn’s basement studio, Hawkins began laying the framework for his new record along with the help of Taj Mahal, James Burton, Ry Cooder, and Paul Murphy. Hawkins had established a practice of playing with up and coming musicians when he successfully enlisted the help of a young James Burton for the twangy signature lick on “Suzie Q”, and things were no different this time around with youngbloods Ry Cooder and Taj Mahal along for the ride. Hawkins would later travel to Memphis, TN where he worked with Dan Penn, Spooner Oldham, and Wayne Jackson & the Memphis Horns at Ardent Recordings and then to Tyler, Texas where Hawkins hunkered down in a funky little studio and finished the record with the help of Texas Garage Rock obscurites Mouse & The Traps. When all was said and done he had managed to lay down ten slices of pure swamp-funk genius, even getting songwriting help along the way from Bobby Charles of “See You Later Alligator” fame and the writer of “The Letter”, Wayne Carson. Pretty impressive.

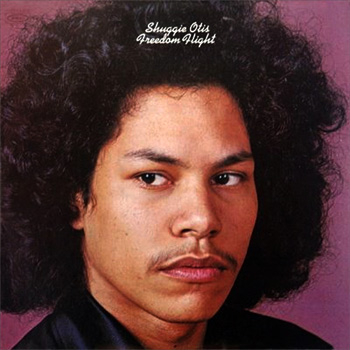

L.A, Memphis, and Tyler, Texas sounds like the front cover looks. That is to say, laid back, down-home, stoned, and restless all at once–it’s a deep fried oddball of an album that takes the genre to new levels and doesn’t sound exactly like anything else out there. The closest points of comparison for Hawkins’ funky noise would no doubt be the kindred spirits of Jim Ford, Link Wray, and Bobby Charles, although the kinda eerie haunted vibe that possesses part of the album brings to mind Skip Spence’s acid masterpiece “Oar” more than the music of Dale’s cousin Ronnie Hawkins or Dale’s former Chess Records labelmates. Simply put, L.A, Memphis, and Tyler, Texas is weird, in a totally wonderful way.

The title track is an instant southern juke joint dance floor classic–throw it on the turntable and watch the hips begin to shake! A perfect introduction to the record, right on par with the title track off of Jim Ford’s excellent “Harlan County” lp; the equation begins with an undeniably funky Levon Helm-esque drum beat and ends with a fat and brassy horn part courtesy of The Memphis Horns, with some slinky slide guitar from Ry Cooder and some twangin’ tele from James Burton thrown in for good measure. “Heavy On My Mind”, co-written with the help of Carson, has a great muggy southern vibe and rollicks along at a brisk pace, aided by more excellent guitar work from his young dream team of killer pickers.

Things get freaky on “Ruby, Don’t You Take Your Love To Town”, a song about a disabled Vietnam vet and his unfaithful wife, which Kenny Rogers later scored a hit with. Along with the help of his friends in Mouse & The Traps, Hawkins managed to record a version of this song that really nails the subject matter. It’s deep, dark, murky, and weird, like a bad trip put to wax. Hawkins and the boys must have been chowin’ down on some mighty strange gumbo in that funky little Texas studio to cook up something this chewy. Meanwhile, Bobby Charles co-write “La-La, La-La” is a catchy little winsome pop ditty, and “Little Rain Cloud” is a swamp masterpiece that simply must be heard to be believed. The only place Hawkins comes close to missing the mark is on his cover of the great Jimmy Reed’s “Baby What You Want Me To Do”, which falls just short of the high level of excellence set by Reed’s original version. Nevertheless, the tune fits in pretty perfectly with the freaked out funky vibe of the whole album.

The late 60’s and 70’s were a time when handfuls of great record producers such as Alan Parsons, John Simon and Jack Nitzsche were spending time on the other side of the glass recording albums of their own. Hawkins’ background as both a musician and a producer allowed him to make a record that’s distinctive and exciting in “L.A, Memphis, and Tyler, Texas”. There was nothing like it before, and nothing’s come along since. Dig in, y’all.

“Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love To Town”

![]() Original Vinyl | 1969 | Bell | search ebay ]

Original Vinyl | 1969 | Bell | search ebay ]

![]() CD Reissue | 2006 | Revola | buy here ]

CD Reissue | 2006 | Revola | buy here ]