Various Artists “Zabriskie Point Original Soundtrack”

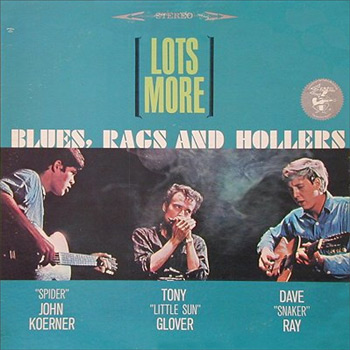

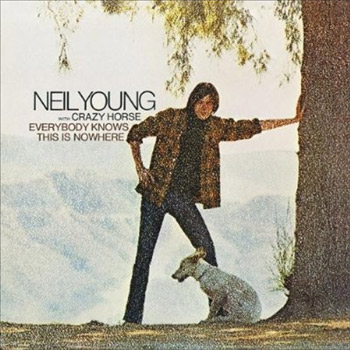

All three major American counterculture movies of the late sixties benefitted from the new vogue for rock soundtracks. The Strawberry Statement mixed purpose-written orchestral themes with mostly familiar numbers by CS&N and Neil Young, plus the predictable but appropriate Something In The Air and Give Peace A Chance. Easy Rider thrummed along to a more eclectic but still fitting selection from Dennis Hopper’s record collection: Steppenwolf, Hendrix, the Byrds and stoned oddities from the Holy Modal Rounders and the Electric Prunes. But maverick director Michelangelo Antonioni’s choices for Zabriskie Point are more enigmatic, and the story of their choosing more bewildering.

The film itself, part wilfully perverse take on the late sixties student unrest, part classic road movie and part soft-porn skinflick, has been analysed to death; you either love it or hate it. The soundtrack album by contrast has received few reviews and deserves examination in these pages. The story goes that Antonioni commissioned the then hot acts Pink Floyd, John Fahey and Kaleidoscope (US) to create new music for various scenes in the film including the notorious desert love scene, which they duly did, and then summarily rejected almost all of this when delivered, instead delving into the back catalogues of these acts and others. (According to legend, the spurned Fahey was so affronted he decked the director forthwith.) The lengthy, dusty love scene was eventually orchestrated by Jerry Garcia’s solo guitar improvisations, and even then Antonioni insisted on a fussy edit compiled from four different improvs for the final seven-minute opus.

Perhaps the oddest thing is that despite all these creative shenanigans the soundtrack still works, both in the movie and as a long-player. Floyd’s opening Heart Beat, Pig Meat is an organ-driven sound collage that contains enough menace to convey the tension as the students discuss the upcoming strike, and their soft, Byrdsy Crumbling Land provides a fleeting but apt background to the start of Daria’s desert odyssey in the Buick though, as Dave Gilmour admitted, it could have been done better by any number of American bands. A brief spiralling segment of the Dead’s live Dark Star accompanies Mark’s liftoff of the stolen Cessna from the airfield at LA, while Fahey’s Dance Of Death, which is somewhat discordant but isn’t actually very morbid, plays after Daria hears over the radio of Mark’s gunning-down by the cops on his return to the airfield. Patti Page’s venerable Tennessee Waltz is an inspired choice for the old rednecks in the desert truckstop (and would cost Antonioni a small fortune to licence from the State, which owned the copyright). Garcia’s sweet, restrained playing provides a genuinely sensitive background to the balletically-choreographed desert orgy. And of course the explosive climax is tailor-made for Floyd’s climactic Careful With That Axe, Eugene, which appears in a re-recording unfortunately inferior to the wonderful original single B-side and with the alternative title Come In Number 51, Your Time’s Up. The two Kaleidoscope tunes Brother Mary and Mickey’s Tune, Roscoe Holcombe’s down-home I Wish I Was A Single Girl Again and the Youngbloods‘ Sugar Babe are all excellent, delightfully obscure country rock items which accompany various highway scenes out in the Mojave.

The movie also featured Keith Richards’s bluesy You Got The Silver, which for licensing reasons never appeared on the OST album, and Roy Orbison’s splendid but inappropriate So Young which played over the closing titles and was allegedly added at post-production without Antonioni’s permission, and is hence with some justification also omitted. The 2-CD Sony reissue offers on its first disc all the other soundtrack tunes in complete form apart from the truncated Dark Star, and on the other the four complete Garcia improvs and four pieces of the rejected Floyd material, most of which are interesting enough but sound rather raw and unfinished, presumably not having being polished up for the final takes, and hence really for Floyd completists only. The CD booklet offers as cover picture a bizarre solarised still of the film’s two principals au naturel and a really excellent essay on the soundtrack by David Fricke.

“Crumbling Land”

![]() Original Vinyl | 1970 | MGM | search ebay ]

Original Vinyl | 1970 | MGM | search ebay ]

![]() CD Reissue | 2010 | Sony | buy here ]

CD Reissue | 2010 | Sony | buy here ]

![]() Spotify link | listen ]

Spotify link | listen ]