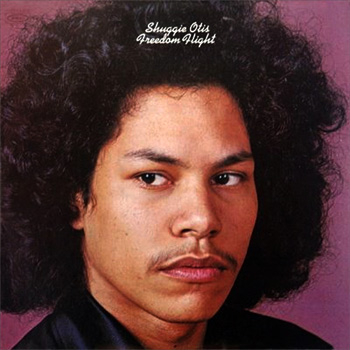

Shuggie Otis “Freedom Flight”

As we all know, the oldest cliché in rock is the casualty list. There are the high-profile heroes of misadventure: Buddy Holly, Hendrix, Stevie Ray Vaughan. There are those that couldn’t handle success and took the ultimate way out: Nick Drake, Kurt Cobain, Jeff Buckley. But perhaps saddest of all are those huge talents who unaccountably chose simply to fade into obscurity, often in self-imposed seclusion: Brian Wilson, Peter Green, Emitt Rhodes . . . and Shuggie Otis.

Johnnie Velotes Jr was a precocious musical polymath. Son of extrovert jump-jive bandleader Johnnie Otis, Shuggie inherited the musical gene in spades, playing guitar, bass, drums, keyboards and vibes fluently before reaching his teens. At fifteen he replaced Mike Bloomfield in Al Kooper’s occasional all-star supergroup for the album Kooper Session: Al Kooper Introduces Shuggie Otis. In the same year he played bass on the sessions for Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats; that’s Shuggie’s bubbling, syncopating bass on Peaches En Regalia.

A year later the teenage prodigy released his first solo album, Here Comes Shuggie Otis, co-written and produced by his father and backed by the cream of Johnnie Sr’s session pals. The second followed a year later: its title Freedom Flight symbolised Shuggie’s breaking loose from his father’s patronage, with most compositions being credited to him alone and with a much smaller coterie of backing players, while Shuggie overdubbed his own bass and keyboard parts and wrote his own string and brass charts. But even this new level of creative control wasn’t enough: his third and final album, Inspiration Information, took three years to construct, with Shuggie playing everything bar the horns and strings which he scored. And then, at the age of 22, Shuggie Otis went into self-imposed retirement. Apart from occasional studio sessions for other artists and, recently, some low-key live appearances in Northern California, he’s remained silent and invisible.

The first album is an enthusiastic freshman romp through blues and funk, showcasing Shuggies’s youthfully exuberant guitar; the last is an introspective, sensitive effort that unites soul and jazz in what would now be called ambient soundscapes, way ahead of its time but with a curiously vulnerable, unfinished quality. Freedom Flight is undoubtedly his most-realised collection. The blues/funk axis carries over from Here Comes, notably on the killer opener Ice Cold Daydream and the sole cover, Gene Barge’s Me And My Woman, but with a far more mature, considered approach to his guitar playing from the eighteen-year-old virtuoso. The album also nods in other directions; the gorgeous psychedelically-tinged California soul of Strawberry Letter 23 with its astonishing coda, the restrained modal slide guitar work on Sweet Thang and the guitar/flute dialogue that ends the joyous Someone’s Always Singing. But the big surprise is the title track, which moves unexpectedly into the most melodic of free jazz with the guitar improvising against tenor sax, Fender Rhodes and a ubiquitous wind chime for thirteen minutes, and not a wasted note anywhere “ Shuggie’s absolute masterpiece. This points toward the third album, and the direction he’d probably have taken thereafter had he stayed the course.

One reviewer called Shuggie Otis the link between Sly Stone and Stephen Stills; personally I’d say between Mike Bloomfield and Curtis Mayfield. But such comparisons are subjective and irrelevant. If you want to follow up this brilliant, enigmatic young musician’s brief career on CD, Inspiration Information was reissued on David Byrne’s Luaka Bop imprint in 2001 with four key tracks from Freedom Flight included as bonus cuts, while the first two albums reappeared in full as a twofer on the excellent Raven label from Australia in 2003. Both releases are unreservedly recommended.

“Strawberry Letter 23”

![]() Original Vinyl | 1971 | Epic | search ebay ]

Original Vinyl | 1971 | Epic | search ebay ]

![]() CD Reissue | 2003 | 2fer | Raven | at amzn ]

CD Reissue | 2003 | 2fer | Raven | at amzn ]